The English translation is below

学習者の皆さんは、日本のマンガを読んだり、テレビを観た時に

猫がしゃべると「ちがうニャ」犬がしゃべると「そうだワン」

と語尾が変わるのをどう受けてめているのでしょうか。。。

個人的にはめちゃめちゃ便利だと思っています♪

キャラクター語尾というのは、文の最後につけて

話し手の性格や雰囲気を強く見せる言い方です

内容よりも「どんな人が話しているか」を伝えますが

日常会話で使うことはほぼないですね。

ふざけてマネして言うことがあるくらいです

でもその語尾を見ただけで、聞いただけで

絵や映像がなくてもどんな人が話してるのか

一瞬で分かるんですよ!

これは日本社会の中でステレオタイプが

共有されているからです

具体的に見てみましょう

「〜じゃ/じゃよ」高齢男性•老人キャラ

少し古風で、知識を感じさせます。名探偵コナンの

阿笠博士も使ってますね

『わしじゃよ、新一』

「〜ござる」忍者、武士が使う言葉です

『忍者は修行でござる』

「〜ザマス」鼻持ちならない金持ち•教育ママ

この辺になると、実際耳にすることすらないんですが…

イメージぴったりなのがドラえもんのスネ夫ママ!

『スネちゃま、おやつのお時間ざます!』

『今日は塾ざますよ!』

「〜て/てよ」お嬢様 時に高飛車

『よくって?』というのは、いいですか?いいかしら?

くらいの意味です。このマンガは50年くらい前のものなのですが

ちゃんと現代でも通用してます

『好きになってもよくってよ』

→あたくしのことを好きになってしまうのは男性なら当然というか

仕方のないことだから、いいわ、許してあげてよ。

でもあたくしはあなたのような庶民は相手にしなくってよ」

。。。という意味を含んでいます(笑)

これまでの語尾はカテゴリーを示すものでしたが

この語尾なら、この人!と限定されるものもあります

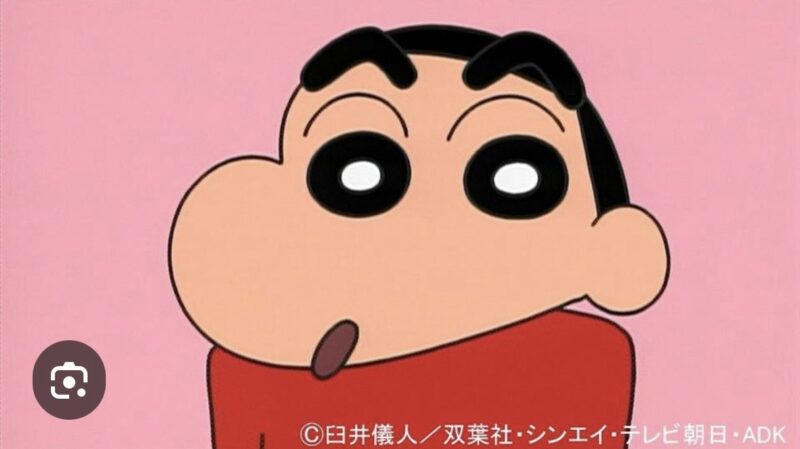

例えば『クレヨンしんちゃん』の「〜ゾ/だゾ」

『オラは人気者だゾ』『たいして誰も気にしてないゾ』

『キテレツ大百科』のコロ助 「〜ナリ/ナリよ」

『コロッケは世界一おいしいナリ』『さよなら、は言わないナリよ!』

『うる星やつら』のラムちゃん「〜だっちゃ」

『ダーリン、浮気はダメだっちゃ!』『わかってるっちゃ』

『一生かけても言わせてみせるっちゃ』

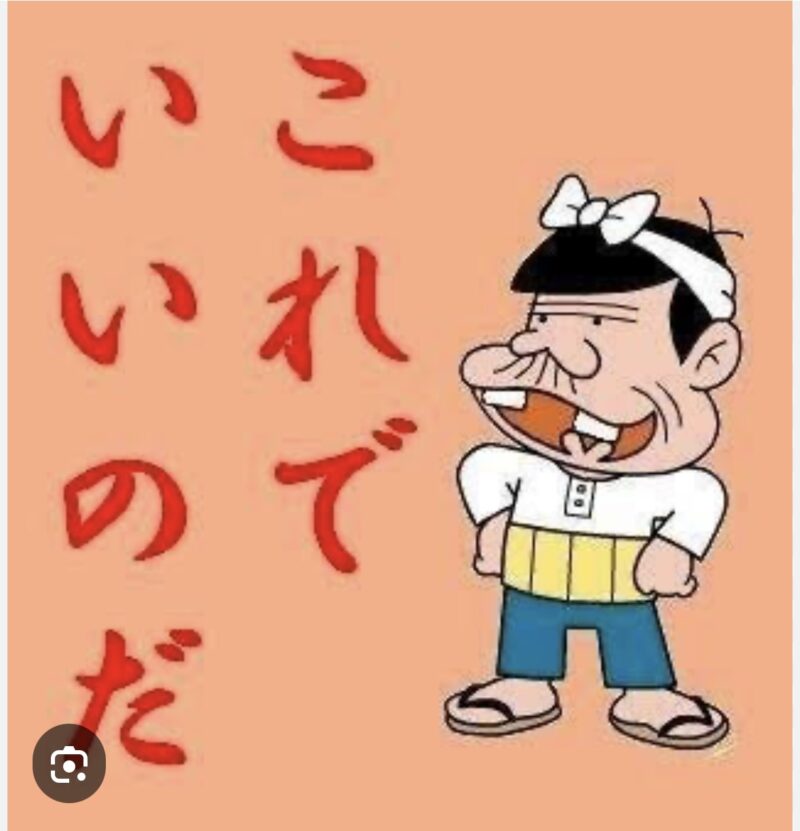

『天才バカボン』のバカボンのパパ「〜のだ」

これは人生の名言です!

AIの出現で外国語を学ぶ必要性はこの先だんだんと

なくなってくるのかもしれません。

でもこういう語尾は、翻訳になるとどうしても元の

ニュアンスを失ってしまいます

私も長年、英語、スペイン語を学び続けていますが

やはりオリジナルの言語で理解できる楽しさ

ホンモノが分かる喜びは捨てたくはないと思っています

来年も、共に楽しみながら語学を学んでいきましょうね♪

「今年も大変お世話になったナリ」

「また来年だっちゃ!」

「良いお年をなのだ〜〜!」

I wonder how learners of Japanese feel when they read manga or watch TV shows from Japan and notice that characters change their sentence endings depending on who is speaking.

For example, when a cat talks, it says “chigau nya,” and when a dog talks, it says “sou da wan.”

Personally, I find this kind of expression extremely convenient.

Character-based sentence endings are expressions added to the end of a sentence to strongly show the speaker’s personality or atmosphere.

Rather than conveying information, they tell us “what kind of person is speaking.”

In everyday conversation, they are hardly ever used.

People may imitate them jokingly, but that’s about it.

However, just by seeing or hearing these sentence endings, you can instantly imagine who is speaking — even without pictures or video.

This is because these stereotypes are widely shared within Japanese society.

example.

“~ja / ~ja yo” is a sentence ending often associated with elderly male characters.

It has a slightly old-fashioned feel and suggests wisdom or knowledge.

Professor Agasa from Detective Conan is a well-known example.

“Washi ja yo, Shinichi.”

“~gozaru” is a sentence ending associated with ninja and samurai characters.

It sounds very old-fashioned and is almost never used in modern everyday speech.

“Ninja wa shugyō de gozaru.”

“~zamasu” is a sentence ending associated with snobbish wealthy characters or overbearing “education-minded” mothers.

At this point, it’s not something you would ever hear in real life.

A perfect example is Suneo’s mother from Doraemon.

“Sune-chama, it’s snack time, zamasu!”

“Today is cram school day, zamasu!”

“~te / ~te yo” is a sentence ending associated with “ojō-sama” characters — refined young ladies, sometimes with a slightly arrogant tone.

The phrase “yokutte?” roughly means “Is that acceptable?” or “May I?”

This manga was published about fifty years ago, so this way of speaking sounds outdated today.

That said, it can still work even now when used intentionally.

“Suki ni natte mo yokutte yo.”

This implies something like:

“It’s only natural — or unavoidable — that a man would fall in love with me, so yes, I’ll allow it.”

“But someone ordinary like you is not someone I would seriously consider.”

(laughs)

Up to this point, the sentence endings we’ve seen mainly indicate a general character type.

However, some sentence endings are so distinctive that they immediately point to a specific character.

A good example is “~zo / da zo” from Crayon Shin-chan.

“Ora wa ninki-mono da zo.”

“Taishite dare mo ki ni shite nai zo.”

In Kiteretsu Daihyakka, Korosuke uses the sentence endings “~nari / ~nari yo.”

These endings are not tied to a general category, but are strongly associated with this specific character.

“Korokke wa sekai ichi oishii nari.”

“‘Goodbye’ is not something I say, nari yo!”

In Urusei Yatsura, Lum uses the sentence ending “~dat-cha.”

“Darling, cheating is not allowed, dat-cha!”

“I understand, dat-cha.”

“I’ll make you say it, even if it takes my whole life, dat-cha.”

In Tensai Bakabon, Bakabon’s father uses the sentence ending “~no da.”

“Kore de ii no da.”

This line has become a famous life quote in Japan.

With the rise of AI, it may be that the need to learn foreign languages will gradually decrease in the future.

However, expressions like these sentence endings inevitably lose their original nuance when translated.

I myself have continued studying English and Spanish for many years, and I still feel that the joy of understanding something in its original language — the happiness of truly “getting it” — is something I don’t want to give up.

So next year as well, let’s continue enjoying language learning together.

“Thank you so much for everything this year, nari.”

“See you next year, dat-cha!”

“Have a wonderful New Year — no da~~!”