The English translation is below

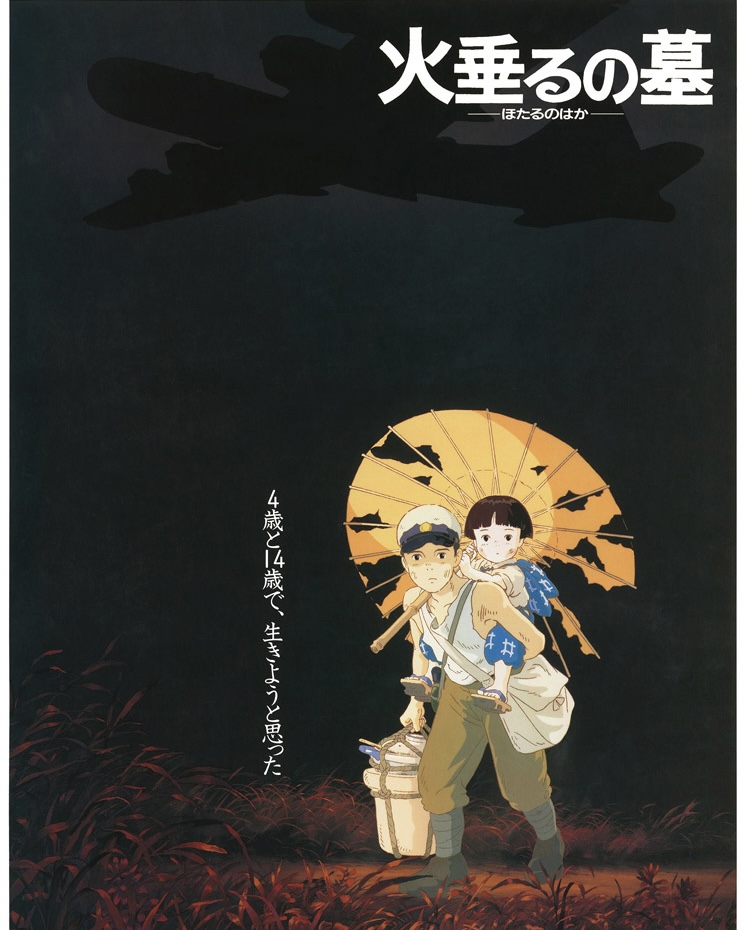

火垂るの墓は、1988年に公開されたスタジオジブリ制作の映画です

昨年Netflixにおいて190カ国で配信が始まったため、観た人もいる

かもしれません

1945年、第二次世界大戦の神戸が舞台です。

空襲で家と母親を失った清太と節子の兄妹は、親戚の家に

身を寄せるも疎まれ、やがて2人だけで防空壕で暮らし始めます

過酷な状況下、2人の絆は深まる一方で次第に食糧は尽き…

私はこの映画を観るのをずっと避けてきました

観た人の感想を聞いたりすると、わざわざ悲しい思いを

したくなかったし、重苦しい気分にもなりたくなかったし…

でも今年は戦後80年の節目でもあり、ちょうど終戦記念日の

8月15日にテレビ放送があったので録画して、もちろん1人で

ティシューと飲み物を用意して観てみました

涙することもなく、淡々と観終わったのですが

直後の感想としては、『何だかなぁ…』という気分でした

どうしてこんな結末になっちゃたんだろう…

もっと生きる道はあったんじゃないかって今でも

モヤモヤしています

親戚宅で手伝いもせずにいたら、おばさんが不機嫌になってくる

のも分かります。お父さんが戻ってくるまでの短期間であろうと

楽観視していたのかもしれませんが。

お母さんが残してくれた貯金も今の価値でいうと70万位ありました

それもあってか冷たくされた親戚の家を出ていくことにしましたが

そうなると配給も受けられません。お金があっても食糧が手に入らない社会で

物資や人とのつながりの方が生存にはずっと重要だったんですよね

ただ、裕福な家庭のボンボンにしては、清太のサバイバルスキルは

なかなかでしたね!目の前の池かなんかを上手く活用していました

節子のことをとてもよく面倒をみていたのは認めます

年が10も離れていると、兄というよりありゃ〜親代わりですね

でも、だんだん節子が栄養失調になって弱っていっても

作物を盗んだり、空襲のどさくさで勝手に家に入って盗みを

働いても、頭を下げておばさんの所へ戻ることはしませんでした

節子が亡くなった後、清太がおかゆとスイカを食べたと思われる

シーンが映ります。まだ生きる意志はあったみたいですね

その後、節子を火葬してから次につながるシーンは

清太が餓死寸前で駅に座り込んでいる映像

何で? まだお金使い切ってないよね?

それなりのサバイバルスキルもあったよね?

節子がいなくなった今、もう自分のことだけ考えればいいんだよ!

清太の心情が描かれずに一気にそこへ飛ぶものだから

急すぎてついていけません。これもモヤモヤの原因の一つです

結局、消極的に餓死を選んだ自殺といえるのかな、と思います

節子を失った後、徐々に清太の生きる意志は蝕まれていって

節子の後を追った、時間差の心中なのかもしれません

幽霊となって再会した二人が幸せそうで、

それだけが救いでしたよ

ただ、当時(1988年)の街並みを見下ろしているという

ことは、二人は成仏できていないということを物語っています

この映画は、反戦映画でも、泣かせ映画でもないと

高畑監督も言っています。大衆娯楽ではなく芸術作品として

観た人が自分の立場で考えて、いろんな解釈ができるんだと思います

清太が戦争下の環境に適応できなかったというのが

1番の悲劇なのかもしれないけど、14歳にそれを求めるのは

酷だよなぁ…

この状況下で、こんなふうにしか生きられなかった兄妹の物語

。。。として受け入れるしかないのかな、と思っています

“Grave of the Fireflies” is a film produced by Studio Ghibli, released in 1988. Since it began streaming on Netflix in 190 countries last year, some of you may have seen it.

Set in Kobe in 1945, during World War II, the story follows siblings Seita and Setsuko, who lose their home and mother in an air raid. They take refuge at a relative’s house, but are treated coldly, and eventually begin living on their own in an abandoned air-raid shelter. Under these harsh conditions, their bond grows stronger, even as their food supplies gradually run out…

I had been avoiding this film for a long time. Whenever I heard people’s impressions of it, I just didn’t want to put myself through that kind of sadness, or end up feeling weighed down…

But this year marks the 80th anniversary of the end of the war, and since it was broadcast on TV right on August 15th, the day of Japan’s surrender, I decided to record it—and finally watch it. Of course, I made sure to be alone, with tissues and something to drink at hand.

I didn’t end up crying, and just watched it through calmly. But right afterwards, my feeling was more like, “I don’t know… it’s hard to put into words.”

I still find myself wondering, “Why did it have to end like that…?” Even now, I can’t help feeling there must have been some other way for them to survive, and that thought still lingers with me.

I can understand why their aunt grew irritated when they stayed at her house without helping out. Maybe they were being overly optimistic, thinking it would only be a short time until their father returned.

Their mother had also left behind some savings—worth about 700,000 yen in today’s money. Perhaps because of that, they decided to leave their relative’s cold household. But once they did, they could no longer receive food rations. In a society where money couldn’t buy food, connections and access to supplies were far more vital for survival.

Still, for a pampered boy from a wealthy family, Seita actually showed some pretty decent survival skills! He made clever use of the pond nearby, for example. And I have to admit, he took really good care of Setsuko. With a ten-year age gap, though, he was less like a brother and more like a stand-in parent.

But even as Setsuko grew weaker from malnutrition, Seita never went back to his aunt’s house. Instead, he chose to steal crops or sneak into houses during the chaos of air raids, rather than swallow his pride and return to her.

After Setsuko passed away, there’s a scene where Seita is seen eating rice porridge and watermelon. It seems he still had the will to live, at least a little.

Afterwards, following Setsuko’s cremation, the next scene shows Seita sitting at the station, on the verge of starving to death.

Why? He hadn’t even spent all his money yet, right? He had some survival skills, too, didn’t he? Now that Setsuko’s gone, all he has to do is look out for himself!

Since Seita’s feelings aren’t shown and the story jumps straight to that point, it feels too sudden to follow. This is one of the reasons why I felt so unsettled.

In the end, I can’t help wondering if it could be seen as a kind of passive suicide by starvation. After losing Setsuko, Seita’s will to live seemed to erode little by little, and perhaps what we’re seeing is a time‑lagged double suicide—him following her, in a way.

Seeing the two of them reunited as spirits, looking so happy together, was the only real comfort for me.

However, the fact that they are shown looking down over the city as it was in 1988 suggests that they haven’t truly found peace.

Director Takahata himself has said that this film is neither an anti-war movie nor a tearjerker. I think it’s meant to be seen as a work of art rather than popular entertainment, allowing each viewer to reflect from their own perspective and come up with various interpretations.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy is that Seita couldn’t adapt to life under wartime conditions—but expecting that of a 14-year-old is just too harsh…

I guess I have no choice but to accept it as the story of a brother and sister who could only live this way under such circumstances…